HKCO

Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra Environmental, Social and Governance Artistic Director and Principal Conductor for Life Orchestra Members Council Advisors & Artistic Advisors Council Members Management Team Vacancy Contact Us (Tel: 3185 1600)

What's On

Concerts

Education

The HKCO Orchestral Academy Hong Kong Youth Zheng Ensemble Hong Kong Young Chinese Orchestra Music Courses Chinese Music Conducting 賽馬會中國音樂教育及推廣計劃 Chinese Music Talent Training Scheme HKJC Chinese Music 360 The International Drum Graded Exam

Instrument R&D

Eco-Huqins Chinese Instruments Standard Orchestra Instrument Range Chart and Page Format of the Full Score Configuration of the Orchestra

40th Orchestral Season

Champions in Concert II

Mong Man Wai Mong Pui Yee Perlie Charitable Foundation proudly supports

8:00 pm

Guanzi: Ma Wai Him

Championing Crossover

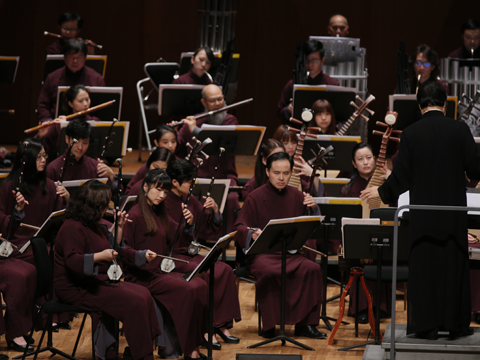

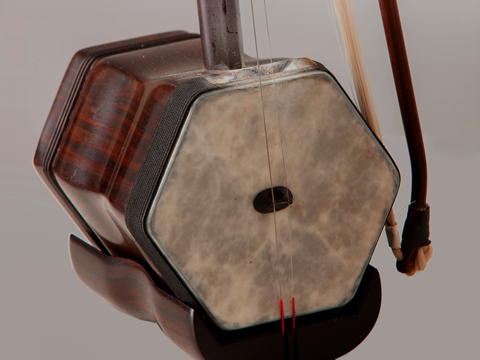

It’s an evening of champs, where talents from far and wide come together to make music. At the helm is the young conductor, Xue Yuan, first-prize winner of the 2nd International Conducting Competition for Chinese Music. He will bring to the audience two amazingly different feasts. The programmes of the two concerts truly know no bounds, as they are taken from both the traditional and the modern/ contemporary repertoires. Zhao Jiping’s The Silk Road Fantasia Suite is a description of China’s exotic West, and features HKCO young virtuoso, Ma Wai Him, winner of the Silver Award in the Folk Instruments section at the 16th Osaka International Music Competition in Japan, and champion and representative of the Hong Kong region. Traces 5 is a musical depiction of four types of Chinese calligraphy written by Wen Deqing. The dynamic brush strokes will be transformed into musical notes on the erhu, performed by Lu Yiwen, winner of the Gold Award at the Erhu Competition which was part of the Chinese Golden Bell Awards for Music 2015. The two concerts promise to be a fine mix of music written by paragons of East and West, performed by talents who shine in supernova glory!

7/10

Silk Road Jiang Ying

Guanzi Concerto The Silk Road Fantasia Suite Zhao Jiping

As the Moon Rises Ancient Melody Arr. by Peng Xiuwen

Becoming a Butterfly in a Dream Chen Ning-chi

Luan-Yun-Fei adapted from the Peking Opera Azalea Mountain Arr. by Peng Xiuwen

8/10

Moonlight on the Spring River Ancient Melody Arr. by Peng Xiuwen

The Insect World Doming Lam

Erhu Concerto Traces V Wen Deqing

Pictures at an Exhibition (Excerpts) Mussorgsky Arr. by Peng Xiuwen

Heritage and Modernity, East and West

Your Support

Friends of HKCO

Copyright © 2025 HKCO