HKCO

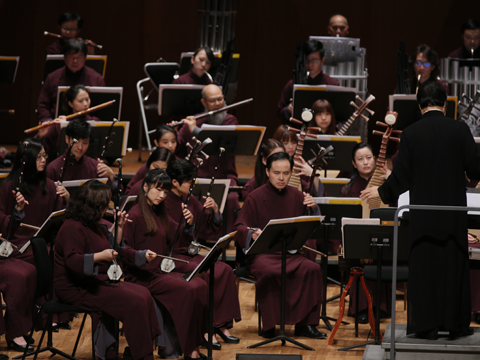

Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra Environmental, Social and Governance Artistic Director and Principal Conductor for Life Orchestra Members Council Advisors & Artistic Advisors Council Members Management Team Vacancy Contact Us (Tel: 3185 1600)

What's On

Concerts

Education

The HKCO Orchestral Academy Hong Kong Youth Zheng Ensemble Hong Kong Young Chinese Orchestra Music Courses Chinese Music Conducting 賽馬會中國音樂教育及推廣計劃 Chinese Music Talent Training Scheme HKJC Chinese Music 360 The International Drum Graded Exam

Instrument R&D

Eco-Huqins Chinese Instruments Standard Orchestra Instrument Range Chart and Page Format of the Full Score Configuration of the Orchestra

40th Orchestral Season

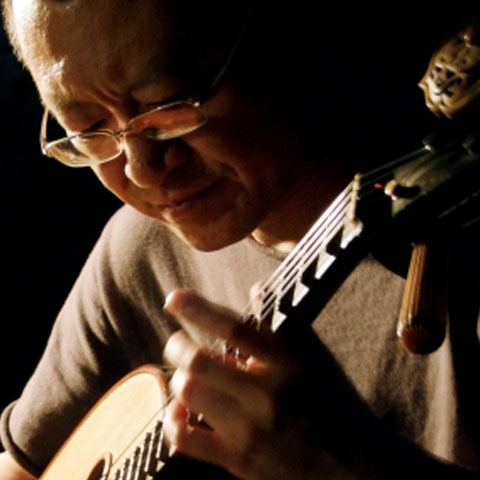

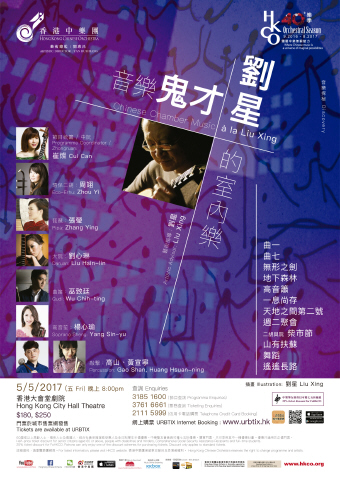

Chinese Chamber Music, à la Liu Xing

8:00 pm

Programme Coordinator: Cui Can

Pipa: Zhang Ying

Zhongruan: Cui Can

Daruan: Liu Hsin-lin

Dizi: Wu Chih-ting

Soprano Sheng: Yang Sin-yu

Percussion: Gao Shan, Huang Hsuan-ning

Tracks of afearless avant-gardist from China

Liu Xing, Chinese composer dubbed “the pioneer of Chinese music in the new age”, cuts an audacious figure in the field because of his unique, non-conformist approach to music-writing. In 1987, he rocked the Chinese music world with his zhongruan concerto, In Remembrance of Yunnan, which was the first ever of its kind. It stood apart from other compositional schools and was regarded as an epoch-making piece. In the thirty years that followed, Liu continued his explorations, foraying into Chinese folk music, symphonic music and New Age music. His works are essentially steeped in Chinese traditional culture but at the same time,exude the forward-looking audacity of a visionary of our age. This upcoming concert features Chinese chamber music from Liu’s wide-ranging oeuvre. Technically challenging and idiosyncratically flamboyant, the programme will definitely rewrite your perception of ‘Chinese music’!

- Music 1

- Music 7

- Dance

- The Underground Forest

- Tuesday Gatherings

- One Last Breath

- A Long, Long Road

- The Invisible Sword

- Erhu & Ruan Chai-Shi-Jie

- There is Mulberry on the Mountain

- Soprano Xiao

- Between Heaven and Earth No.2

A Meteor But Not – on Liu Xing the Composer

Chow Fan-fuIn Chinese transliteration (hanyu pinyin), a meteor is spelt as liú xīng. Like a meteor, composer Liu Xing and his works are dazzling. But unlike a meteor, the brilliance of neither the man nor his music is ephemeral. The dozen or so pieces selected for this concert originated from five of Liu’s earlier CD albums, released between 1991 and 1997, but have been arranged for chamber orchestra. In other words, Liu’s compositions have all been through, and survived, the test of time. Although two decades actually represent a very short test for an art form like music, this passage of time nonetheless proves that Liu’s style of music is nothing like a flash in the pan.

The Early “Prototypes”

The Underground Forest, Tuesday Gatherings and Chai-Shi-Jie are tracks in Liu’s first CD album To Do Nothing (CD No. KIIGO KG1003), and were composed by Liu between 1978 and 1982 when he was studying at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. This album, which opened up a new avenue for Liu, was his first New Age product released under the Hugo Productions (Hugo) label in 1992, after recording concluded in November 1991. It is quite evident that this budding collaboration with Hugo was an exploratory effort to establish a new direction, a ‘Chinese New Age music’ that would ride on the growing popularity of New Age music in the West.

Such an opening for Liu was even more evident in the 1993 album, My Way (CD No. KIIGO KG1006), which contained the tracks One Last Breath and A Long, Long Road. In it, his hallmark personality traits were even more distinct.

With Indefinable (CD No. KIIGO KG1008) in 1995, which included Music 1, Music 7 and Dance (originally Music 6), Liu’s own brand of New Age music took a quantum leap. This continued with the New Age albums The Lake (CD No. MS21002), co-produced by Liu Xing and his friends in 1996 (which included the tracks There Is Mulberry on the Mountain and The Invisible Sword), and The Tree (CD No. MS21003) in 1997 which included Soprano Xiao.

Rapid Maturation

The music in the five albums mentioned here maps the rapid progression, from exploration to maturity, of Liu’s understanding of the New Age genre. His New Age works all feature the electronic synthesizer, which he used together with selected Western and traditional Chinese instruments. While the eleven tracks in To Do Nothing showed signs of awkwardly deliberate efforts, and fell short of being contrived with some of them even

sounding like a rehash of older content, soon these teething problems were overcome, and Liu’s idiosyncratic traits came across distinctly in the eleven tracks of his next album, My Way.

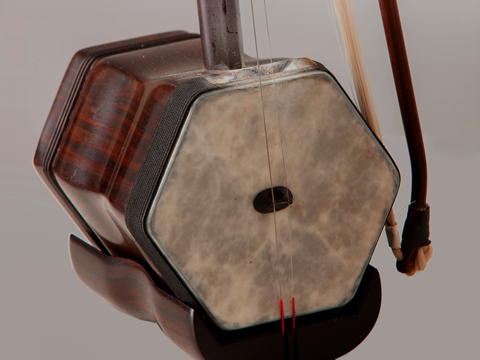

In To Do Nothing, Liu’s instrumentation choices were obviously Chinese bent: guzheng, erhu, zhonghu, pipa, yangqin, dizi, liuqin, zhongruan etc., and this lent the music a strong traditional Chinese flavour. Then in My Way, the choices were limited to zhongruan, dizi, bawu, xiao, and pipa, which pared down the Chinese music character. By the time he produced Indefinable, the Chinese colour had practically disappeared from the music, with the mix of the electronic synthesizer, oboe, violin xun (ocarina) and Du-xiao (a flute-type instrument developed specially by soloist Du Chong). The latter two were the only Chinese instruments used and such instrumentation took away totally the ‘Chineseness’ in the music.

Nor was that all: Liu kept meticulous notes about his thoughts and feelings throughout the creative and recording process for each track of To Do Nothing. With My Way, Liu provided the track titles only after the studio work was complete. His music notes were in short phrases, like verse, recording his moments and his feelings. It was as if he felt strained to do it. So by the time he produced Indefinable, he simply refused to write anything, not even to give titles to his works.

The Story behind Indefinable

This had caused some disgruntlement from Aik Yew Goh, Hugo’s producer and recording engineer, who went so far as to write about it in the print media. Aik was right from a marketing point of view. How could one sell new releases without any music notes as background? As the then General Manager of the company, I was caught between Liu and Aik. We tried several proposals, and finally decided to name the album Indefinable, to make it so abstract that the listener was left to his/her own imaginings. As a desperate move to sell it, we designed and created several add-ons: each track in the Indefinable album came with a card. It had a photo by Aik on one side, and an abstract oil painting by Zhou Kai, a young Chinese artist contracted for Hugo at that time, on the other. In addition, there was a short poem by Pu Tong (the nom de plume I used in my younger days to pen modern poetry), with the Chinese version on the photograph side, and the English translation on the painting side. These may well be described as the emotive or cerebral outcome knocked off from listening to the ten tracks of music by Aik, Zhou and myself, expressed through photography, painting and verse. Very subjective, you’d say, but inevitable, of course.

In fact, we could empathize with what Liu was thinking. The tracks in Indefinable were almost devoid of any ethnic colour. The feelings conveyed were without any specific tonality or imagery; they were international and universal in the sense that they transcended nationalities, religions and borders. In other words, in creating the music for this album, Liu Xing had truly understood that New Age music should not only go beyond the national boundaries but also be free from unnecessary textual guides or directions. His aim was to provide a New Age musical space for listeners to immerse themselves completely in self-participation, with the absolute freedom to let their imagination roam at will.

All said and done, the release of Indefinable was delayed by a year-and-a-half. To eliminate superfluities, the tracks were simply referred to as Music 1, Music 2 and so on. The accompanying images and poems were also untitled. They merely provided the consumer with the opportunity to compare the feelings the music and the other three types of creativity evoked as we were hoping that they would not destroy what Liu Xing had intended.

When Indefinable was re-released much later, the new edition changed to the normal CD album format. The ten-tracks-ten-cards design was replaced by a booklet. This obviously meant that the scope for imagination would be a lot less. Perhaps this story behind the production of Indefinable holds the ‘key’ to truly appreciating Liu Xing’s original creations, and explains why the appeal of his music is not transient or short-lived like a meteor. (For this reason, I strongly recommend that the audience refrain from listening to the five early Liu Xing CDs beforehand, in particular not Indefinable. The works in the concert are not what they were, because as chamber music, the instrumentations and arrangements have become totally different.)

Your Support

Friends of HKCO

Copyright © 2025 HKCO